"Writers do well when we cast ourselves as villains"

A Q&A with Sanjena Sathian

Jhumpa Lahiri’s fiction, Sanjena Sathian argued in Issue Four of The Drift, is defined by “patient, pretty prose,” and “quiet insights.” Lahirism, as Sathian calls it, is intimately tied to respectability politics. “Coming first meant that hers became the way to write brown books,” Sathian continues, “a fact that loomed over me.”

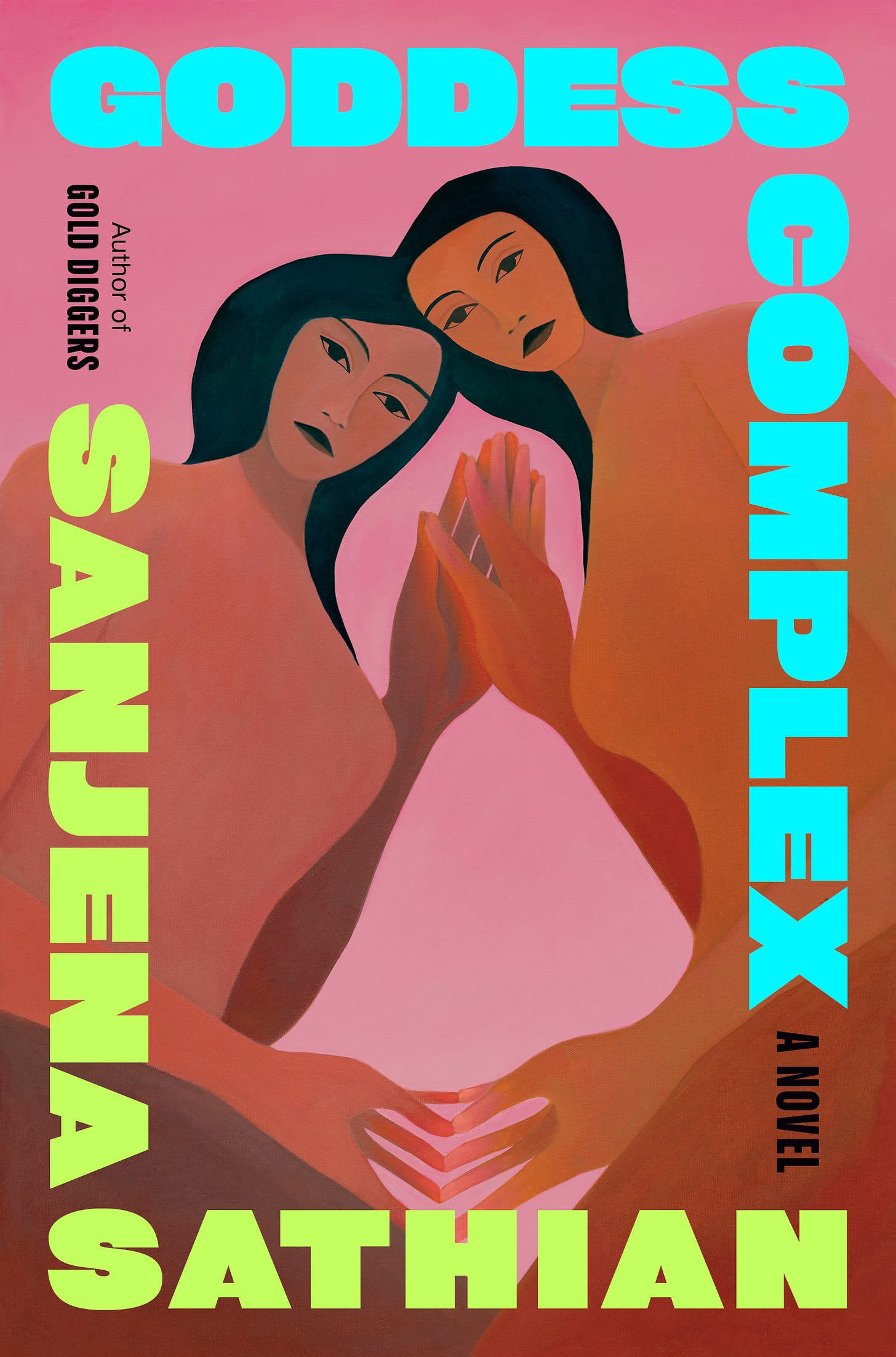

Sathian’s own second novel, Goddess Complex, out today, isn’t afraid to let its characters and insights get loud. Our essays editor, Lyra Walsh Fuchs, talked to Sathian about being both a critic and a fiction writer, social novels, doppelgängers, Rosemary’s Baby, and more.

Is it difficult to turn off your inner critic when you’ve put out argumentative pieces about what good fiction is and isn’t? In other words, how do you separate ideas about writing from the act itself?

For a long time, the work of the critic and the work of the novelist seemed distinct to me: fiction meant trying to make stuff, and criticism was (I believed) a deconstruction, the anti-creation. But as I read more criticism, I realized that I was wrong; criticism — even of the “takedown” genre — is itself productive, not destructive, because it helps writers and readers understand what fiction can and should be. I now find that writing criticism actually helps me clarify my own intentions. I teach, too, and running workshops does something similar: it helps me read myself better.

I also think I approach criticism as a novelist first. Last fall I published a piece about “#MeToo social thriller” movies. I had thrown away a very different version of Goddess Complex that relied on a #MeToo social thriller-esque gimmick. My personal experience made me sympathetic to the aims of the writers and directors whose work I was examining. I also understood the temptations that led some of them to make choices I consider lazy.

But ultimately, I write a few pieces of criticism a year. When I’m working on them, I live almost entirely with my critic brain for a few weeks or months. When I’m done, I exit the critical world by reading a lot of older novels that have nothing to do with contemporary discourse. I’ve gotten better at switching back and forth.

Goddess Complex seems to flirt with the autofictional mode, or at least invite readers to wonder about your relationship to its narrator, who is named Sanjana Satyananda. She becomes obsessed and then entangled with a woman with an eerily similar face and name to her own: Sanjena Sathian. Why did you choose to give the antagonist your name, and the narrator its parallel?

The book isn’t autofiction, as you know from how it unfurls. It shares more with the metafictional Operation Shylock than, say, a Rachel Cusk novel, and of course, it’s working in the tradition of doppelgänger stories rather than autofiction. I actually used my own name the first time I wrote a doppelgänger story — long before I’d heard the term “autofiction.” It was a story called “Catfishing in America,” about a woman named Sanjana Satyan who met a woman calling herself Sanjena Sathian; Sanjena-with-an-e usurped Sanjana-with-an-a. Assigning my name to the villain was like something a mischievous doppelgänger would do. It was just fun.

In an early draft, Goddess Complex’s narrator was the Sanjena-with-an-e character, which was a mistake. When I wrote as Sanjena-with-an-e, I felt awkward, like I was assigning too much of myself to this figure. Zadie Smith has written that first person narrators are “the I who is not me,” and early versions of Sanjena-with-an-e were not “not me” enough. In the end, Goddess Complex’s narrator, Sanjana-with-an-a, is the I who is not me, and Sanjena-with-an-e is the me I’m afraid of — the me I could become, but not the me who exists now. In general, I think writers do well when we cast ourselves as villains as well as sympathetic figures. It helps prevent sanctimoniousness (or so I hope).

Goddess Complex doesn’t mention Trump, but abortion and the desire (or lack thereof) for motherhood do figure heavily in the plot; at one point, the narrator is inspired by the “Shout Your Abortion” movement to blurt out the word at a baby shower. Would you say that Goddess Complex is a social novel? What do you think is the role of the novel in digesting the political concerns of the day?

I agree that this is a social novel, but I didn’t set out to write a social novel. I began this book during the first Trump term, and it wasn’t about abortion at all. It was just about a bad relationship crumbling. Eventually, I asked myself why the relationship crumbled, and I settled on the way the binary “baby decision” — to procreate or not — can divide couples, and even friends and communities. That led me to abortion, because I wanted to write someone who is so close to parenthood that she gets pregnant semi-intentionally, but changes her mind.

The novel turned outward at that point, inevitably. An overeducated character like Sanjana was always going to engage with the political discourse around abortion while processing her own pregnancy. If I have anything to say about the “issue” of reproductive choice, it’s that the way we talk about the politics of motherhood and childbearing is patently absurd, and in turn makes people behave absurdly. That’s what I like about social novels: they can both take political ideas seriously and explore the ways public discourse renders private life absurd. They’re about the gray space between public language and private life.

I noticed that Goddess Complex contained a lot of explicit and implicit references to Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby. How did it emerge as a citation? What else were you reading or watching as you wrote?

Thank you for mentioning the novel Rosemary’s Baby. I feel like people mostly refer to the movie — which I also encountered first — but the book is great. I read and listened to it while writing Goddess Complex. Ira Levin’s narration helps us see the way Rosemary justifies her own pregnancy to herself: She begins by justifying her own rape, and ends up deciding to love her son, the spawn of Satan. It’s a bold, bonkers, dark satire.

I read (and reread) lots of books about pregnancy and choice: Sheila Heti’s Motherhood; Emi Yagi’s Diary of a Void, about a Japanese office worker faking a pregnancy in response to a pronatalist society; and Belle Boggs’s The Art of Waiting, a critical memoir about fertility, among many others. Doppelgänger stories mattered, too: I mentioned Shylock; also Rebecca. For voice purposes, I reread Mating and The Bell Jar to spend time with two of my favorite first-person narrators, and Dorothy Baker’s Cassandra at the Wedding. As for watching: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, the original The Stepford Wives (also based on a Levin novel), Dead Ringers, The Wicker Man, and a lot of Hitchcock.