Close reading angry political posts about Love Island

Plus two poems about TV

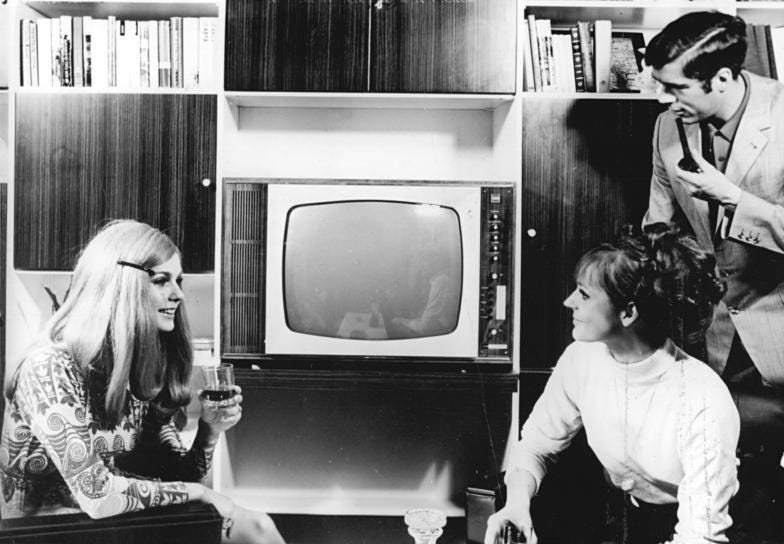

The internet is now the primary target of polemics about the deranging consequences of communications technology, but as Jimmy Kimmel discovered in dramatic fashion last month, television — the old bête noire of Neil Postman and David Foster Wallace — still retains its ability to make people lose touch with reality. As the second week of the new season of Love Island Games draws to a close, Associate Editor Saliha Bayrak looks back on the latest installment of the franchise’s American edition, and the outsized scrutiny fans have begun to apply to contestants’ political views.

For more reflections on the place of television in our troubled psychic life, and the parasocial relationships we develop with the people on our screens, check out two poems from Issue Fifteen below: “List of Programs Broadcast by CNN, Late Winter 2021” by Sasha Debevec-McKenney, and “Streaming” by T. J. Cusano.

The promise of public participation has been central to the allure of reality television since the format surged in popularity around the turn of the millennium. While the first modern reality hit, MTV’s The Real World (1992-2017), kept viewers as passive as they would have been watching any scripted show, Big Brother (which premiered in the U.S. in 2000) transformed them into active co-creators. In its inaugural season, the audience voted on which contestants would be removed from the competition, and ultimately decided on the final cash prize winner. In the 2010s, a new dating show based on a similar premise appeared first in the U.K. and then in the U.S. and across the globe: Love Island. After the first U.K. iteration, 2005’s Celebrity Love Island, failed to gain the public’s favor, its later, more successful spinoff instead recruited regular (hot) people to mingle on screen until the audience voted for its favorite couple.

Over time, viewers have become more and more interested in meddling with contestants’ personal lives, and on the latest U.S. season of Love Island, singles were subject to an unusual level of scrutiny regarding their politics. On social media, fans obsessively investigated the beliefs and loyalties of each participant — discovering that the hunky TJ Palma followed Andrew Tate on X, or that Florida resident Austin Shepard had re-shared pro-Trump videos on TikTok. Loyal followers of Huda Mustafa, a Palestinian American, were devastated to see her make out with Elan Bibas without being informed that he was a Zionist who had previously posed with an IDF soldier for a photo posted on his Instagram. “Sideye-ing the FUCK outta love island production for casting that zionist scum Elan and allowing him to get near Huda when she don’t know his true identity,” one user commented on X.

This consternation is all the more striking because Love Island is intentionally designed to sequester its contestants from reality. The singles mingle with each other hundreds of miles from their homes on a remote tropical island for six to eight weeks with no contact from the outside, wearing an identity-flattening uniform: a swimsuit accessorized with a mic pack. Their cultural and class backgrounds, as well as their political beliefs, are rarely a point of discussion on screen (exceptions are conspicuous, like when one contestant in the U.K. version asked whether Brexit meant “we won’t have any trees”). To hear the Islanders tell it, these omissions are what make romance possible: “The perfect way of meeting someone is being taken away from the world,” Love Island UK season one contestant Jon Clark told Vanity Fair. “Taken away from your friends, your family, all the infiltrating parts that sometimes ruin relationships.” Accordingly, relationships flourish in the villa and fall apart outside. (Multiple interracial couples that had seemed like perfect matches on screen, for example, have called it quits on the outside after one partner encountered racism from the other.)

But despite the producers’ best efforts to keep politics offscreen, reality television personalities have become an expanding target for political grievances. As Anton Jäger theorizes in a 2024 New Left Review essay, popular interest in politics has increased since the 2008 financial crisis (seen in higher voter turnouts and mass protests), even as involvement in durable political institutions has declined (a drop in membership for unions, clubs, political parties, religious organizations). Jäger calls the resulting landscape “hyperpolitical.” Today, hyperpolitical engagement is characterized by constant agitation and low-cost, low-entry, short-term action that evokes the “fluidity and ephemerality of the online world,” leading to little or no structural change. Think someone angrily posting, “so we have not 1, not 2, but 3 tr*mp supporters in the villa? and one of them is british…… this is a nightmare,” as they continue to watch the latest episode of their favorite show.

This summer, I shamelessly followed both Love Island USA and the online behavior of its fans, whose reactions dictated the fate of the islanders in far away Fiji. After digging through years’ worth of Instagram posts and podcast appearances, viewers uncovered that Yulissa Escobar and Cierra Ortega had used slurs against black and Asian people, respectively, leading to widespread backlash. After Escobar was removed from the show, netizens started a hate campaign — characterized by posts like “Let’s hold Cierra accountable for using a racial slur !!! get that girl out that damn villa NEOWWW” — that led to Ortega being quietly pulled from set as well. “Cierra said a slur, apparently friends with a racist influencer, and got a white woman in a bonnet running her account... it’s curtains for her,” another user commented, celebrating the hypothesized end of the L.A. influencer’s career.

When no amount of change in public opinion seems to be capable of shifting domestic or foreign policy in this country — six in ten U.S. voters now oppose sending more military aid to Israel, to no avail — it’s easy to understand why people might seek out substitute forms of political expression, like tweeting angrily until a reality TV contestant gets pulled from their show. Unlike in D.C., an eagle-eyed critic can actually alter the course of events in Fiji. After the show’s morality police led their crusade against Ortega, someone even called ICE on her Latino family. Such disproportionate and confused direct action is a natural consequence of spending hours a day aimlessly wandering through an online world oversaturated with debilitating political news without clear direction on how to respond to it.

Fans also saw this season of Love Island USA as a barometer for racial progress. While some viewers were upset that the only black duo was voted off before the finale, others cheered the diversity of the crowned couple: “Amaya and Bryan — both latinos — being the first latino couple to win Love Island USA in the middle of trump’s administration MI GENTE LATINO WE WON.” When I clicked on the post, fully expecting to see the replies mocking this measure of achievement, all I saw was someone complaining about spoilers (the finale had apparently aired just 15 minutes prior): “This truly why we can’t have anything nice in this world.”

We should not delude ourselves into thinking our reality TV interventions are meaningfully changing anything in the real Real World. In spite of volatile responses from viewers, this season received a record high of 8.8 billion minutes of views. Over a million people also tuned into the latest season aired in the U.K. — even as producers received tens of thousands of formal viewer complaints, including objections to its allegedly racially biased editing. We are far too informed and enraged to mindlessly consume trashy, escapist reality television without protest, but not enough to stop watching it. Only at the end of this summer — in the most unexpected of places, the comment section of Facebook reels — did I find a take I could relate to: “Maybe we should hold our political leaders as accountable as we do Love Islanders.”

Saliha Bayrak is an associate editor at The Drift.

List of Programs Broadcast by CNN, Late Winter 2021 | Poetry

SASHA DEBEVEC-MCKENNEY

Every day, I force myself to take an absurdly long walk.

I follow The Lead with Jake Tapper. I am at the park

with Jake Tapper. The lake with Jake Tapper.

T. J. CUSANO

Pirating the latest prestige drama, I am faced with a question:

Do you want to fuck an older woman who lives in your area?