"Ordinary people fall short in recognizable ways"

A Q&A with Madeline Cash

Madeline Cash’s wicked sense of humor is on full display in “Our Lady of Suffering’s Inner Beauty Pageant,” the excerpt we published from her debut novel, Lost Lambs. But Lost Lambs isn’t just funny. Cash’s chronicle of the Flynn family and its dysfunction is animated by a tender appreciation for ordinary, flawed humanity and a sharp insight into the madness of life in contemporary capitalist America. Livia Wood, our associate fiction editor, spoke with Cash about her writing process, her influences, and her tax-advantaged domestic partnership. Lost Lambs is out today from FSG. While you wait for your copy, be sure to read our excerpt online.

Lost Lambs is told from an impressively large number of characters’ perspectives. What was it like to inhabit so many different points of view?

Like Being John Malkovich. Authorship is heretical in that way, because you’re playing God. I thought of each character like a constraint or writing exercise. They come with their own limits, views and misunderstandings. Each character believes they’re telling the story accurately and none of them are entirely right. The accumulation of perspectives is what gets closest to the truth.

Your characters are delightful in part because they are, like most of us, a bit flawed. How did you think about morality in relation to the book’s religious setting and themes?

At its most basic, before it gets institutionalized or weaponized, religion offers a practical moral baseline: Don’t kill. Don’t steal. Honor your father and mother. Don’t perjure your neighbor. Those are not especially controversial ideas. In Lost Lambs, the religious framework isn’t there to cast judgment or sort characters as righteous or evil. I’m not their moral arbiter. It’s there to illuminate how ordinary people fall short in recognizable ways. They want comfort, forgiveness, relief from pain. They’re products of their upbringings and doing the best they can with the hand they’re dealt. At the risk of sounding like an after-school special, that’s all any of us can do, right?

Early references to things that seem insignificant later return as important aids in this complex story. How did you go about plotting out the novel?

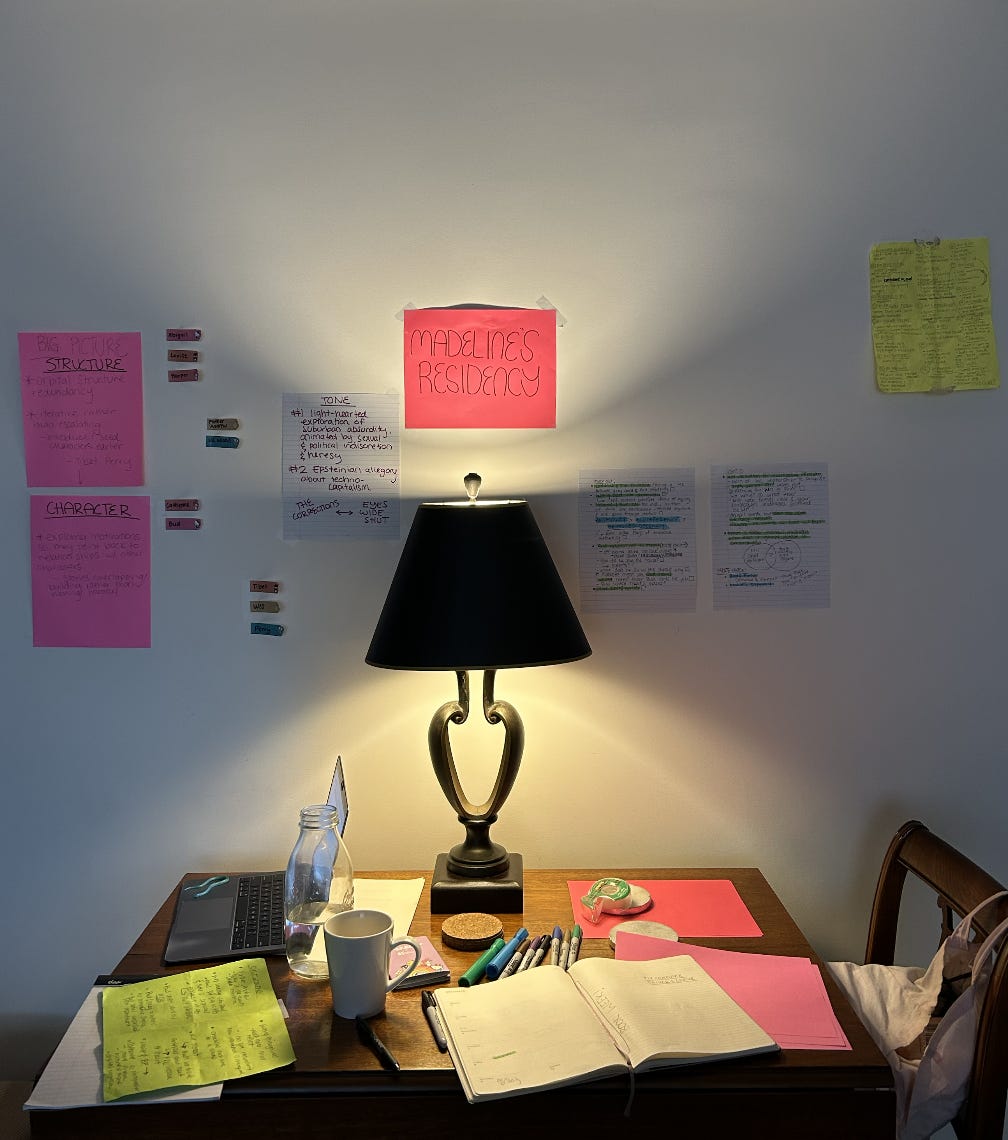

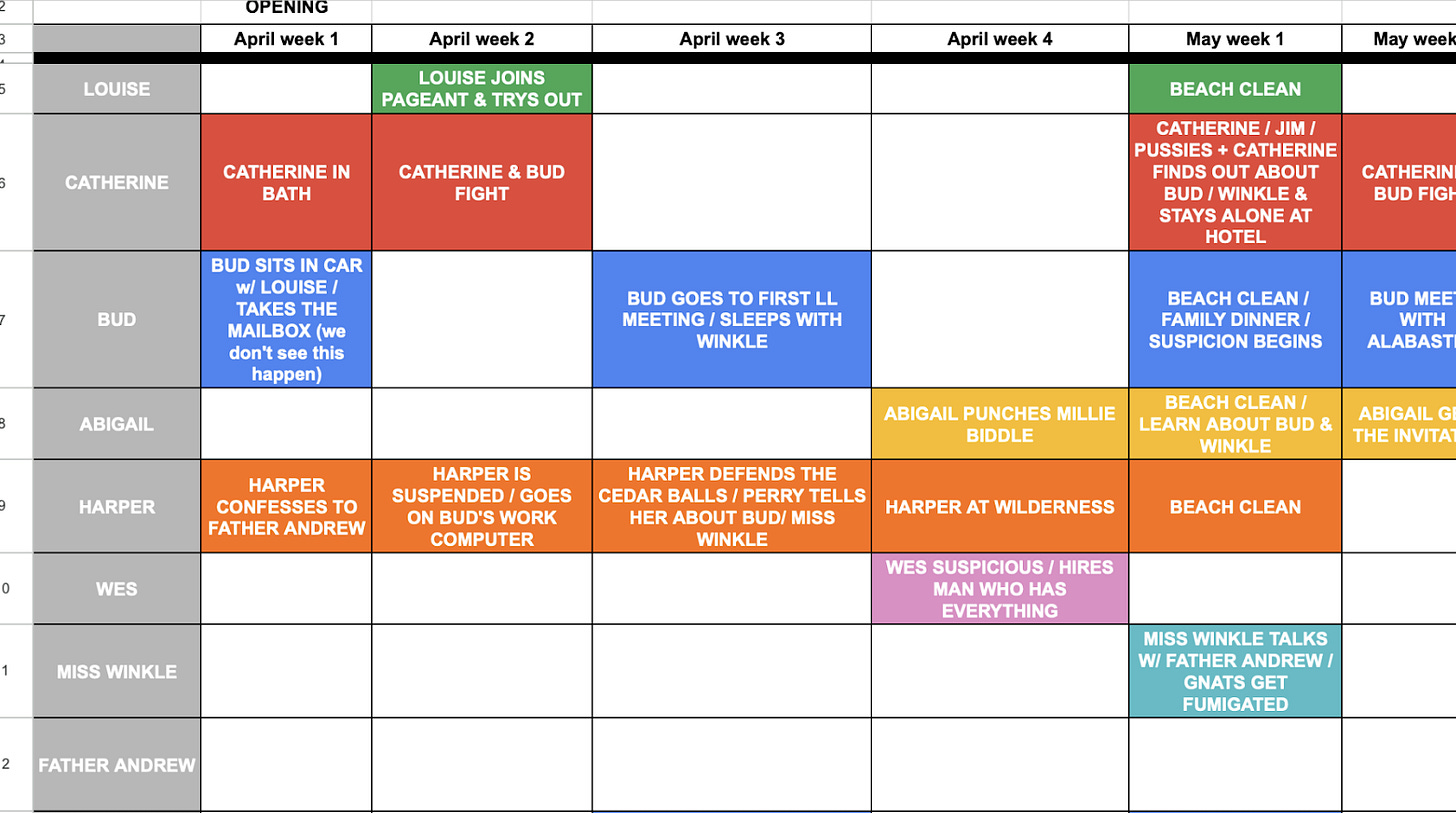

I plotted it out with post-its on the wall and have several spreadsheets. It looked like this:

Love takes up a complicated role in your novel: it’s a source of pain, heartbreak, violence, but it’s also a source of hope, comfort, renewal. As an emotion or experience, it becomes associated with both immaturity and wisdom. At various points, Catherine and Bud are falling in and out of love; both Abigail and Louise are dating, with varying degrees of success, and Harper is beginning to come into herself as a young woman. How did you think about romantic love as you were writing Lost Lambs?

Lost Lambs is not a love story. Marriage is a system like any other (religion, politics) and takes more than infatuation to function. The classic Merchant of Venice quote, “But love is blind, and lovers cannot see the pretty follies that themselves commit,” means, to me, that lovers overlook faults they maybe should not — i.e. Louise falling for an online terrorist, or Catherine falling for her idealized version of the neighbor. Even that word, “falling,” isn’t sustainable: it implies you have to hit the bottom.

The love that truly endures in the book is the selfless kind: one’s love for a child, or for community, freedom, and justice. In the book, Catherine asks, “Am I really the woman of your dreams?” “Who cares!” Bud responds, “You’re the woman of my reality.” It’s function over form. After twenty years of marriage, when the initial butterflies stop fluttering, you’re left with core values, compatibility, ability to compromise or work together. I’m not a total cynic — romance is beautiful and strange and galvanizing. Sometimes gross and unpredictable. Please take my marriage advice with a grain of salt because I am 29 and unmarried. I do have a domestic partnership for tax purposes that’s going quite well.

Lost Lambs feels very contemporary, in part because it touches on so many topical issues: religious fanaticism, open relationships, conspiracy theories. I was especially interested in your exploration of wellness, and particularly the brand of it that has become associated with the right wing and the tech world. How did you go about engaging with that ideology?

When writing the book a few years ago, I was interested in anti-aging gene therapies employed by the super wealthy. In particular, Bryan Johnson (the guy who receives transfusions of his son’s blood, not the lead singer of AC/DC) became a figure of fascination. I wasn’t fascinated with them ideologically — I’m not sure I’d call Paul Alabaster right wing; he’d probably call himself a libertarian or independent or an effective altruist or something — but psychologically. We all fear death but accept its inevitability, until we reach a certain income bracket and begin to question fate, rail against it, etc. I just think that’s interesting.

The family depicted in Lost Lambs could be called unconventional, or blended. Would you use those words? How do you see the family dynamics at play?

Sure, yeah, those are great words. The Flynn family starts off pretty conventional and utterly miserable. My own family dynamics are rather unconventional. I was raised by a single mother and her friends and teachers and people she plays mah-jongg with and several huskies. She’s of the belief that it takes a village to raise a child. I was trying to subvert the American Dream. That sounds kind of pompous — “subvert the American Dream” — but I just mean to say, there isn’t a proper way to assemble a family. It also takes a village to write a book and I thank all of these people: Cait, Josh, Rachel, Cam, Aidan, Rian, and all of my found family.

Your novel strikes me as very singular, but I’m curious if there is any media that was particularly influential on your writing, or that you’d place in dialogue with your work?

Ecclesiastes says there’s nothing new under the sun. So if there was nothing new in nine hundred B.C.E., there definitely isn’t now. A lot influenced my writing: Franzen, fables, Donald Barthelme short stories, Eyes Wide Shut, The Big Sleep — I read many 1930s-1950s noirs to learn how to plot a mystery — The Virgin Suicides movie and book, Henry Darger’s The Story of the Vivian Girls, systems novels like Underworld, the music and world-building of Gorillaz, shipping websites, Reddit, my friends, my Lutheran elementary school.

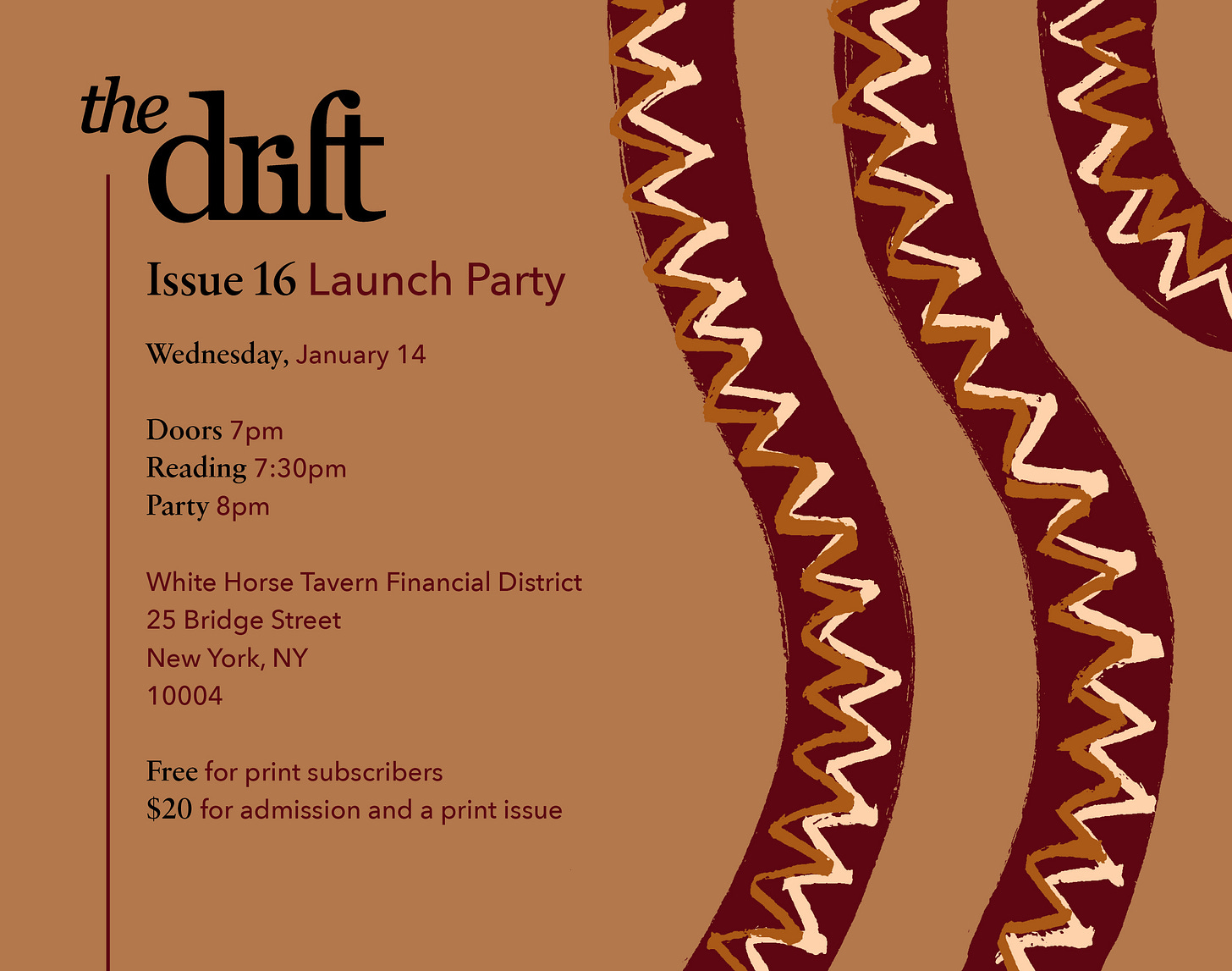

We will be celebrating Issue Sixteen tomorrow at the White Horse Tavern in the Financial District starting at 7 p.m. We hope to see you there!