"The poem is for asking questions and being unsure"

A conversation with Sasha Debevec-McKenney

I grew up eating off the presidents. I got peanut butter on them, then pesto. In the morning, over the sink, my parents would wipe the mess from the laminated educational placemat, returning the 43 miniature portraits of our commanders-in-chief to their plastic purity.

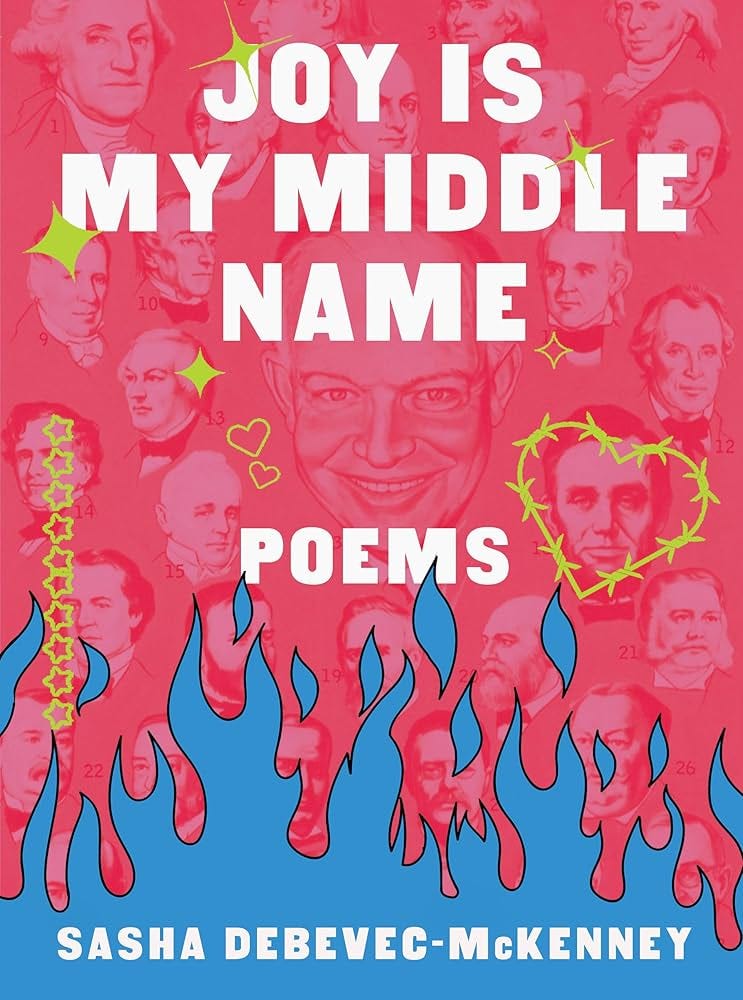

Sasha Debevec-McKenney grew up eating off the presidents, too. She references a similar placemat in “I BRING THE WART REMOVAL KIT WITH ME TO THE JULY 4TH PARTY,” a poem from her debut collection, Joy Is My Middle Name, which knows when to play with its food and when to eat it. The book, out today in the U.S. from Norton, encompasses a history of American leadership, a personal history of sobriety, a decade of life with friends, enemies, and family across the country, and standup comedy — often all on the same page.

Five years ago, in our second-ever issue, The Drift published a poem about a trip Sasha took to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California. And this summer, in our fifteenth issue, we published a poem of Sasha’s that incorporates the titles of CNN broadcasts into a lockdown-era, day-in-the-life narration of self.

One of Sasha’s projects is taking language that might appear empty — meme-ese, a snippet of a conversation overheard, posts on the Reddit forum r/nofap — and following it somewhere deep, filling it up with itself, filling it up with herself. One conviction I derive from Sasha’s work is that to speak about serious topics in an exclusively serious tone would risk being an unserious project, a project afraid of the humor that inheres in all life and all relation. Sasha has no such fear. Her poems speak in the voice of both the wise child who wants to learn, who makes a mess, who wastes nothing on respect; and the learned adult who has lived through something, who knows how to clean up, who earns for herself everyday a stronger self-regard.

I spoke to her about righteousness, found text, and the American presidents.

I’d like to start at the end of the book, where a twelve-page paratextual section called “DEBTS, SOURCES, NOTES” serves as liner notes of a sort for the poems themselves, contextualizing their creation and embarking on additional digressions. It contributes to my sense that there’s very little distance between you, Sasha, and the speaker of the poems in this book. How did you think about constructing the speaker, and the speaker’s voice? Do you think of the poems as nonfiction? As confessional?

The DEBTS, SOURCES, NOTES section was a result of my obsession with Robert Caro’s Lyndon Johnson biographies. His NOTES section was so rich and fun to read, it felt like he just took everything that got edited out of the book and stuck it in the back. And thank god. So I tried to do that — add a little more to the story.

I’m actually obsessed with this question because I wrote the NOTES section with the intention of doing the opposite of collapsing the distance between myself and the speaker. I was trying to show people that I’m lying in the poems. It’s like: here’s everything I lied about! Here are the real facts! The reader should definitely trust the Sasha who wrote the NOTES section more than they trust the Sasha who wrote the poems. The poems are basically emotionally true, but so many of the details are completely made up or smoothed over or stolen or changed for the sake of the story or the joke. The poems are definitely not nonfiction, maybe closer to memoir. You know how in some people’s memoirs they’re writing full scenes about things that happened when they were four? I do not believe they remembered that stuff! But you let them have it. You know what you’re reading is a version of the truth the writer has shaped in their own mind for however many years, not the real truth. I’m not consciously constructing a speaker, I’m constructing a story.

Even as many of the poems deliver clear, artful criticisms of our social mores and political leaders, they also seem to insist on their speaker’s lack of a moral high ground, on a lack of consistent moral clarity. What’s your relationship with righteousness? With self-awareness? How, if at all, did your ethics and politics evolve as you wrote the poems in the book?

I hope my ethics and politics are never stagnant! I just want the reader to trust me (love me?), and if I show them the speaker is imperfect they’ll relate to her more. I’m not perfect and I am always willing to be more educated about basically anything. I worked at this restaurant in Madison called Morris Ramen when it first opened, and my boss Francesca Hong’s motto was “no complacency.” I think about that all the time. I can always be better. I’m not trying to be messy or be like, look at how crazy I am…. I never go into the poem with a ton of big, confident feelings. The poem is for asking questions and being unsure. If you’re on the moral high ground you’re not unsure. And also probably kind of boring and unrelatable. Believe me, I am bitchy and judgmental as a person, and a lot of the poems start from a place of anger — but then they change and get more complicated.

I think my self-awareness in my poems is a result of constantly wondering how I will be perceived in real life. I’m basically constantly in a panic about how I will be perceived. But the poem gives you a chance to be more thoughtful than you are in the real world. In the poem I can take more time to craft the way I want to be perceived. That being said, I’m wildly off all the time. I don’t think anyone would describe me as particularly self-aware. Anyways, I was obsessed with the presidents as a little girl and obviously that obsession has changed since I was a five-year-old demanding my presidents placemat. I don’t know why they interest me; they just do. I’m grateful to my MFA cohort at NYU, because they really helped me think more deeply about the way I write about presidents.

Several of the poems in the collection involve found text: from comedy specials, your own tweets, and Cat Marnell’s book How to Murder Your Life, among other sources. How do you feel about the terms “lowbrow” and “highbrow”? How do you decide what of the world could and should become material for a poem?

It's fun to use a highbrow art form to describe and analyze a “lowbrow” topic. You’re uplifting the lowbrow while disrespecting the highbrow. Poetry gets such a bad rap for being pretentious and impenetrable but I believe it’s for the people. I write about what I think about and I think about reality TV a lot, sorry. (Side note: I hate when people think they’re deep or different for watching, like, The Bachelor or Love Is Blind with a critical eye. Like yeah, duh, that’s why reality TV is popular.) I don’t think I decide what should become material for a poem — the material decides, the poem decides. If you put restrictions on what is “worthy” of a poem then you’ll write fewer poems.

What’s your earliest memory of encountering language that had the quality of poetry to it? (Whether or not it was an actual poem.)

Well, my first favorite poem was Lucille Clifton’s poem called “i am accused of tending to the past.” I also loved Charles Bukowski and Billy Collins, the poet laureates of Borders in 2004. I have no idea where it came from, but when I was a kid, my mom and brother and I used to repeat to each other, “I eat my peas with honey, I’ve done it all my life, it makes the peas taste funny but it keeps them on my knife.” That was my real first favorite poem. I have a tattoo of a knife and honey wand.

Where do you get your sense of humor from?

Ultimately, my sense of humor comes from my mom and my dad, who are both huge readers and jokers. I watched Zoolander every single day of seventh grade. I used to fall asleep listening to the director’s commentary of either The 40-Year-Old Virgin or Superbad or Hot Fuzz. I owned the complete Monty Python’s Flying Circus on DVD and in college I remember being so offended that someone I met with a Holy Grail poster couldn’t name their favorite Python. I didn’t really have lots of friends in high school so I was just torrenting all kinds of weird British comedy. Stewart Lee is my favorite comedian, and I have probably seen all of The Thick of It and Peep Show about ten thousand times each. I watched basically everything Armando Iannucci ever made pre-2012. I really love Nick Lowe and Elvis Costello and all the freaky funny Stiff Records music. I’ve listened to millions of hours of Comedy Bang Bang! I’m basically just a huge comedy dork.

My sense of humor also comes from going to a small liberal arts college in the midwest full of weirdos. From flirting. From working service and doing the same jokes over and over to different customers. Trying to make my best friend Anna laugh, trying to make my little brother Evan laugh. And more than anything, of course, my sense of humor is a result of my desperation to be liked and my need for attention. One time in grad school Terrance Hayes said my poems reminded him of Richard Pryor, which was the highlight of my life.

How would you describe your relationship with your imagination?

My relationship to my imagination is tense and rocky because I have such a severe anxiety disorder. It’s a double-edged sword. I like to write because I never really know what kind of shit will come out of my head… but that’s not always a good thing when you only want to walk around enjoying your life.

Who’s a poet more people should read?

Hera Lindsay Bird, who is a poet from New Zealand. This past June, Deep Vellum released a book of Bird’s work in the U.S. for the first time. Her poems give me such deep joy. I feel so understood by her, despite our never meeting and being born in totally different countries. I also think everyone should read Chessy Normile. She is a genius for real.

Jordan Cutler-Tietjen is an associate editor at The Drift.